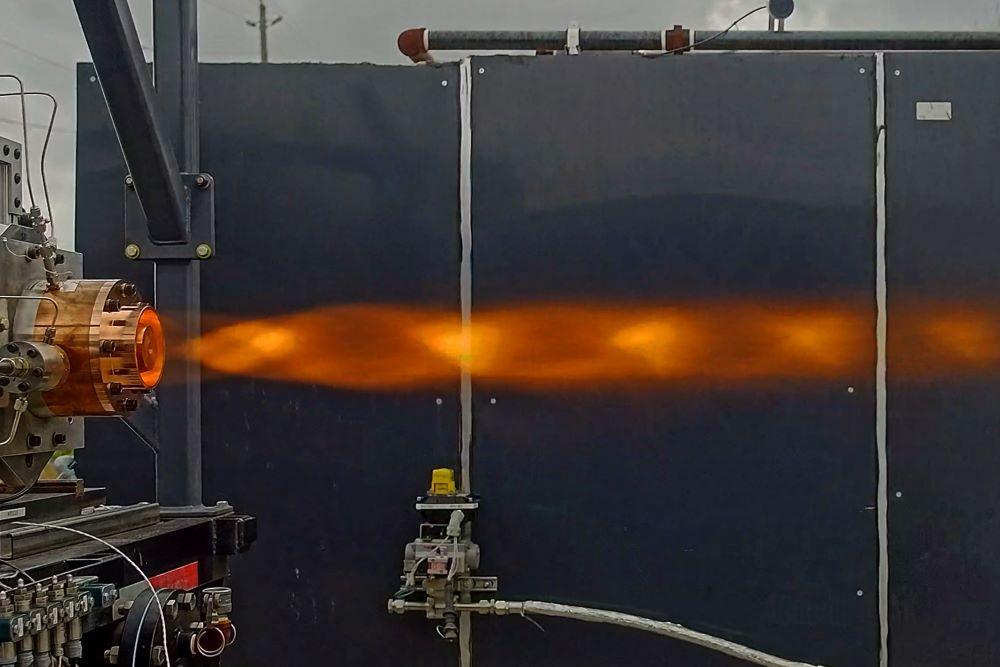

Credit: Venus Aerospace

COLORADO SPRINGS–Rotating detonation engines have huge potential for realizing efficient high-speed flight, but they are proving fiendishly difficult to get right.

In the five short years since focusing on the concept, Andrew Duggleby, chief technology officer and co-founder of the pioneering hypersonic propulsion systems developer Venus Aerospace, says he has learned that five key steps are required to make a detonation engine work.

Number one–get it to detonate without melting it. Number two, use liquid rather than gaseous fuel for the higher pressures that enables. Number three, learn how to deal with the intense heat fluxes. Number four–learn how to make it perform. Finally, number five–get a good nozzle.

Now, after a series of ground rig tests, the Houston-based company says it has that final ingredient–a good nozzle–thanks to help from NASA. Through a NASA Small Business Innovation Research award, Venus tested new nozzle designs for its rotating detonation rocket engine (RDRE) and says, “the top-performing design exceeded expectations and will be integrated into Venus’s ground-based launch test in the coming months.”

“We’ve already proven our engine outperforms traditional systems on both efficiency and size,” Venus CEO Sassie Duggleby says. “The technology we developed with NASA’s support will now be part of our integrated engine platform—bringing us one step closer to proving that efficient, compact, and affordable hypersonic flight can be scaled.”

Through extended ground tests of scaled RDREs, Venus has already progressively tackled key technical issues of the constant volume combustion system, including stability, parasitic deflagration, stiffness and thermal management. As a quick reminder, an RDRE combusts the fuel/air mixture at supersonic speed and in a constant volume–detonating the mixture explosively rather than in the subsonic deflagration process seen in conventional combustors.

The process results in a pressure gain during combustion and takes place over a shorter distance, which reduces the size of the combustor and therefore its weight. Venus wants to demonstrate these efficiencies in the air and build on a successful initial flight test conducted with an 8-ft.-long, 300-lb. drone in early 2024.

The upcoming flight test will be far more ambitious, with hopes of accelerating an RDRE-powered vehicle to a top speed of Mach 5 or more. Such a speed would satisfy the conventional definition of hypersonic flight. Duggleby has his own demarcation: “heat is a dominant issue. I know people say it’s Mach 5. My favorite definition is where heat kicks your ass.”